I was kind of scared when I first read the challenge description, as I had never done a firmware rev chal before.

Overview

I started by trying to get an overall idea of the the various concepts involved, beginning with the Trusted Platform Module (TPM). I watched this video.

Based on my understanding, a TPM is a piece of hardware that does encryption and decryption of data passed to it. It has a "mini-processor" and the key is stored inside it, allowing all operations to occur independently of the actual computer. Hence, it is impossible for an attacker to inject their own code or otherwise interfere with the encryption and decryption algorithms. Neither is it possible to leak the encryption key since it is stored on an entirely different memory chip.

Next, I began researching ways to reverse the firmware dump. My search led to esp32_image_parser on github (some other useful resources I came across are https://github.com/BlackVS/ESP32-reversing?tab=readme-ov-file#firmware and https://olof-astrand.medium.com/reverse-engineering-of-esp32-flash-dumps-with-ghidra-or-ida-pro-8c7c58871e68)

Extracting the firmware ELF

The first thing to do is list the partitions on the firmware dump. This is done with python esp32_image_parser.py show_partitions flash_dump.bin

reading partition table... entry 0: label : nvs offset : 0x9000 length : 20480 type : 1 [DATA] sub type : 2 [WIFI] entry 1: label : otadata offset : 0xe000 length : 8192 type : 1 [DATA] sub type : 0 [OTA] entry 2: label : app0 offset : 0x10000 length : 1310720 type : 0 [APP] sub type : 16 [ota_0] entry 3: label : app1 offset : 0x150000 length : 1310720 type : 0 [APP] sub type : 17 [ota_1] entry 4: label : spiffs offset : 0x290000 length : 1441792 type : 1 [DATA] sub type : 130 [unknown] entry 5: label : coredump offset : 0x3f0000 length : 65536 type : 1 [DATA] sub type : 3 [unknown] MD5sum: 972dae2ff872a0142d60bad124c0666b Doneoutput

To get an idea of what each partition is for, I watched this video. I concluded that the main program code should be in either the app0 or app1 partition.

I tried to dump it using the command python esp32_image_parser.py dump_partition flash_dump.bin -partition app0. This produced the file app0_out.bin. Then I tried to extract it as an ELF using the command python esp32_image_parser.py create_elf flash_dump.bin -partition app0 -output app0.elf. There were a number of errors but looking through the github issues and pull requests I was able to apply the relevant patches to fix each issue. Here are all the patches I applied:

diff --git a/esp32_image_parser.py b/esp32_image_parser.py index 6503cf7..0abcc86 100755 --- a/esp32_image_parser.py +++ b/esp32_image_parser.py @@ -6,6 +6,7 @@ import json import os, argparse from makeelf.elf import * from esptool import * +from esptool.bin_image import * from esp32_firmware_reader import * from read_nvs import * @@ -53,6 +54,7 @@ def image2elf(filename, output_file, verbose=False): section_map = { 'DROM' : '.flash.rodata', 'BYTE_ACCESSIBLE, DRAM, DMA': '.dram0.data', + 'BYTE_ACCESSIBLE, DRAM': '.dram0.data', # hope this works 'IROM' : '.flash.text', #'RTC_IRAM' : '.rtc.text' TODO } @@ -154,7 +156,9 @@ def image2elf(filename, output_file, verbose=False): if (name == '.iram0.vectors'): # combine these - size = len(section_data['.iram0.vectors']['data']) + len(section_data['.iram0.text']['data']) + size = len(section_data['.iram0.vectors']['data']) # + len(section_data['.iram0.text']['data']) + if '.iram0.text' in section_data: + size += len(section_data['.iram0.text']['data']) else: size = len(section_data[name]['data'])git

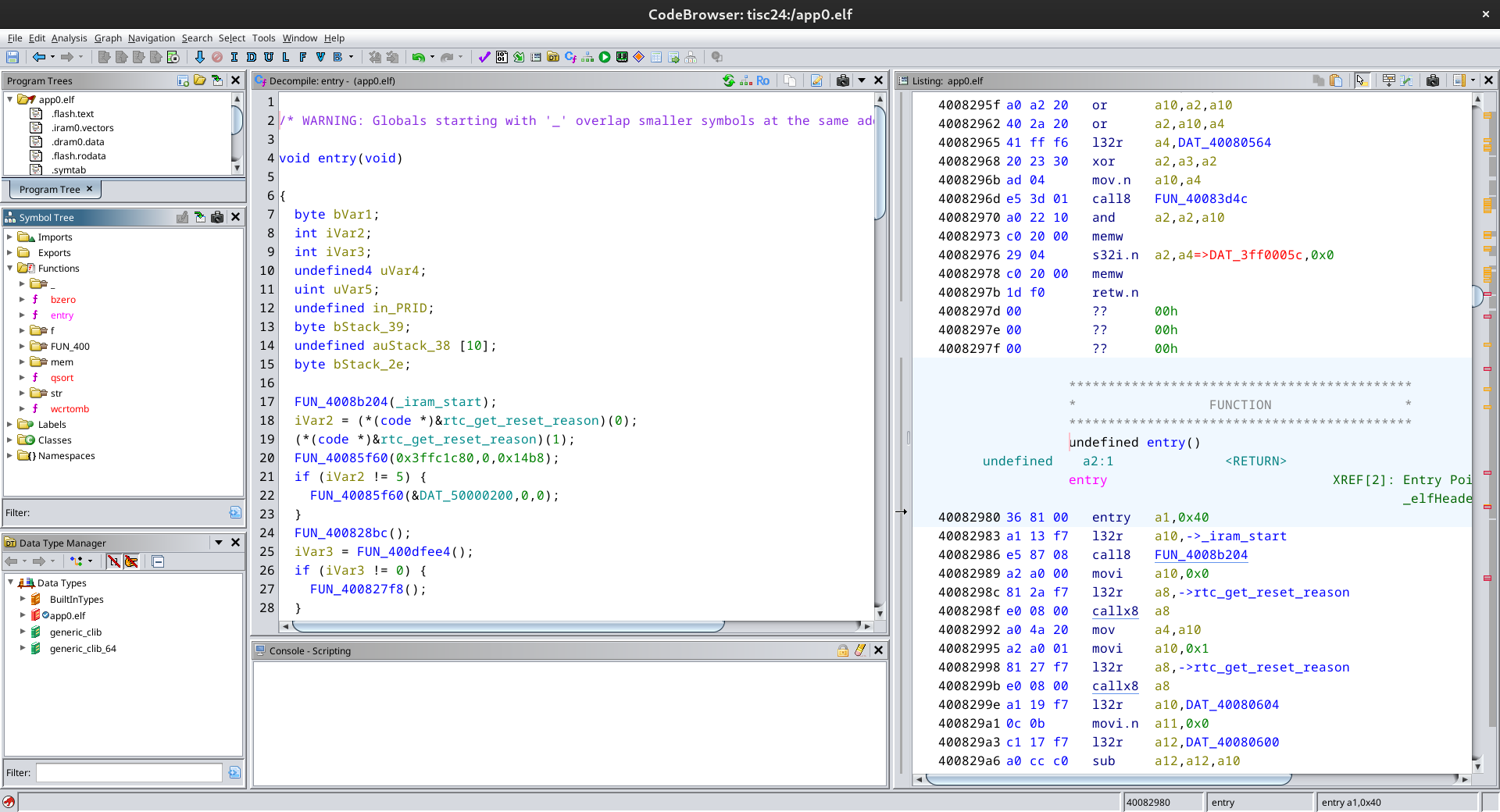

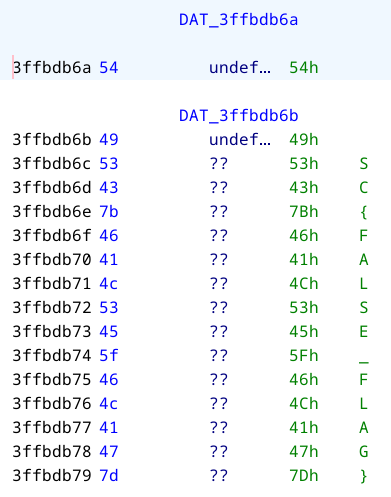

Now, rerunning the command produces an ELF file. To decompile the file with ghidra, I had to install ghidra version 11+ as previous versions did not have support for xtensa esp32 instructions (another option was using https://github.com/Ebiroll/ghidra-xtensa). Now after importing the file into ghidra, we can see the decompilation.

To be honest, I wasn't expecting the decompilation to work since I wasn't even sure if the ELF had been extracted correctly, or if the patches had messed it up somehow. Anyway, I continued on.

Reversing the ELF

The entry function seems to be quite complex and there is no immediately obvious program logic. One good way to locate the program logic is to try and find where readable strings are being used. A strings check on the ELF file yielded a very long list, but one string in particular stood out: BRYXcorp_CrapTPM v1.0-TISC!.

I searched for this string in ghidra using Search > Memory

Following its references, we can see its being used in the following function:

void FUN_400d1578(void)

{

FUN_400d3470(0x3ffc1ecc,0x1c200,0x800001c,0xffffffff,0xffffffff,0,20000,0x70);

FUN_400d3670(0x3ffc1ecc,1);

FUN_400f25bc(0x3ffc1cdc,FUN_400d1614);

FUN_400f25c4(0x3ffc1cdc,FUN_400d15e8);

FUN_400d17d8(0x3ffc1cdc,0x69,0xffffffff,0xffffffff,0);

FUN_400d379c(0x3ffc1ecc,s_BRYXcorp_CrapTPM_v1.0-TISC!_====_3f400120);

do {

DAT_3ffbdb68 = FUN_400d1b04(4);

memw();

memw();

} while (DAT_3ffbdb68 == 0);

return;

}

After looking through the functions (BFS), I came across this one:

/* WARNING: Globals starting with '_' overlap smaller symbols at the same address */

void FUN_400d1614(uint param_1)

{

byte bVar1;

int iVar2;

int iVar3;

byte bVar4;

uint uVar5;

int iVar6;

int in_WindowStart;

undefined auStack_30 [12];

uint uStack_24;

memw();

memw();

uStack_24 = _DAT_3ffc20ec;

FUN_400d36ec(0x3ffc1ecc,s_i2c_recv_%d_byte(s):_3f400163,param_1);

iVar2 = (uint)(in_WindowStart == 0) * (int)auStack_30;

iVar3 = (uint)(in_WindowStart != 0) * (int)(auStack_30 + -(param_1 + 0xf & 0xfffffff0));

FUN_400d37e0(0x3ffc1cdc,iVar2 + iVar3,param_1);

FUN_400d2fa8(iVar2 + iVar3,param_1);

if (0 < (int)param_1) {

uVar5 = (uint)*(byte *)(iVar2 + iVar3);

if (uVar5 != 0x52) goto LAB_400d1689;

memw();

uRam3ffc1c80 = 0;

}

while( true ) {

uVar5 = uStack_24;

param_1 = _DAT_3ffc20ec;

memw();

memw();

if (uStack_24 == _DAT_3ffc20ec) break;

func_0x40082818();

LAB_400d1689:

if (uVar5 == 0x46) {

iVar6 = 0;

do {

memw();

bVar1 = (&DAT_3ffbdb6a)[iVar6];

bVar4 = FUN_400d1508();

memw();

*(byte *)(iVar6 + 0x3ffc1c80) = bVar1 ^ bVar4;

iVar6 = iVar6 + 1;

} while (iVar6 != 0x10);

}

else if (uVar5 == 0x4d) {

memw();

uRam3ffc1c80 = DAT_3ffbdb7a;

memw();

}

else if ((param_1 != 1) && (uVar5 == 0x43)) {

memw();

bVar1 = *(byte *)(*(byte *)(iVar2 + iVar3 + 1) + 0x3ffbdb09);

bVar4 = FUN_400d1508();

memw();

(&DAT_3ffc1c1f)[*(byte *)(iVar2 + iVar3 + 1)] = bVar1 ^ bVar4;

}

}

return;

}

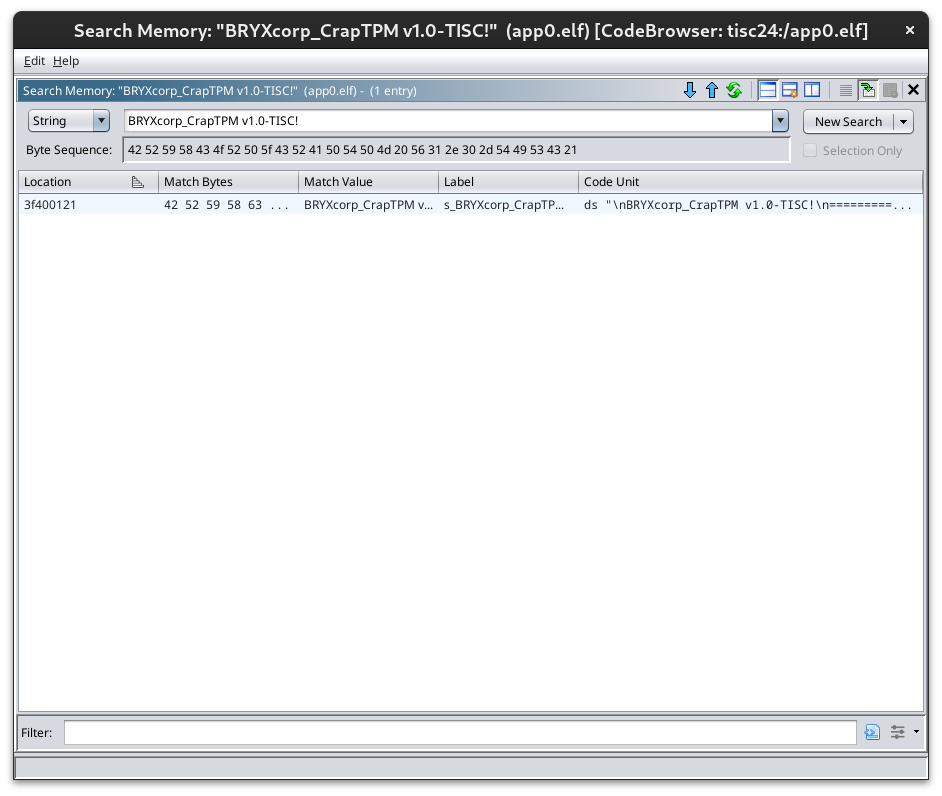

clicking on the DAT_3ffbdb6a symbol I found that it points to an interesting string:

A fake flag! This proves we're on the right track. The function above is probably the main function, and FUN_400f25bc is probably analgous to __libc_start_main?

Let's take a closer look at this branch:

if (uVar5 == 0x46) {

iVar6 = 0;

do {

memw();

bVar1 = (&DAT_3ffbdb6a)[iVar6]; // the fake flag

bVar4 = FUN_400d1508();

memw();

*(byte *)(iVar6 + 0x3ffc1c80) = bVar1 ^ bVar4;

iVar6 = iVar6 + 1;

} while (iVar6 != 0x10);

}

So it's xoring the flag with the output of a mystery function, FUN_400d1508. (It's unclear what is done with the result, but most likely it's being outputted in some way?) Let's have a look at that function:

ushort FUN_400d1508(void)

{

ushort uVar1;

memw();

memw();

uVar1 = DAT_3ffbdb68 << 7 ^ DAT_3ffbdb68;

memw();

memw();

memw();

uVar1 = uVar1 >> 9 ^ uVar1;

memw();

memw();

memw();

DAT_3ffbdb68 = uVar1 << 8 ^ uVar1;

memw();

memw();

return DAT_3ffbdb68;

}

DAT_3ffbdb68 is a 2 byte region of memory right before the fake flag. So it is presumably some sort of global variable that gets updated each time the function is called. I tried to simplify the equation used to update it but failed to do so. However, safe to say that the resulting xored flag is determined based on the starting value of DAT_3ffbdb68.

Now looking back at the main function FUN_400d1614, it's reasonable to deduce that uVar5 is a value supplied by the user, like an opcode of sorts, and if we somehow send 0x46 to the firmware it should return us the xored flag. This xored flag can then be easily brute-forced by trying all 65536 values for DAT_3ffbdb68.

Testing/fuzzing the firmware

Note: when I was doing my testing on the firmware interface provided, I used the following branch for testing.

else if (uVar5 == 0x4d) {

memw();

uRam3ffc1c80 = DAT_3ffbdb7a; // DAT_3ffbdb7a = "BRYXcorp_CrapTPM"

memw();

}

I assumed that passing 0x4d to the firmware would result in the string "BRYXcorp_CrapTPM" being returned.

Now I had to figure out how to interact with the firmware. Here is the firmware interface provided (nc command in chal description):

Looking at the example for SEND, it seems like the first argument is some address or opcode, and the second argument is the payload.

I tried sending SEND 12 4d followed by RECV 4 but I received only null bytes. After some more unsuccessful tries, I decided to see if it was possible to brute force the first argument (after all, it's only 1 byte). I wrote the following python script to do so:

from pwn import * import random t = remote('chals.tisc24.ctf.sg', 61622) t.recvuntil(b'\n\n> ') for i in range(256): t.sendline(f'SEND {hex(i)[2:]} 4d'.encode()) t.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'RECV 10') data = t.recvline() if data != b'00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00\n': print(hex(i)) print(data) t.recvuntil(b'> ')t.py

This printed out the following:

0xd3

b'42 52 59 58 63 6f 72 70 5f 43\n'

0xd4

b'72 61 70 54 50 4d 00 00 00 00\n'

This looks like ascii text! Decoding it does indeed give the string "BRYXcorp_CrapTPM", which means our hypothesis is correct!

However, when I tried SEND d3 46 followed by RECV 16 I received all null bytes. Maybe some of the bytes sent by my script prior to 0xd3 were important? I tried randomizing the order in which I sent the bytes (shuffle range(256)) and now nothing was being received. So indeed, somewhere along the line one or more of the SEND n 4d commands did ... something. But the command with 0xd3 was where we actually got bytes returned.

Applying that logic, I wrote the following script:

from pwn import * t = remote('chals.tisc24.ctf.sg', 61622) t.recvuntil(b'\n\n> ') for i in range(0xd3): t.sendline(f'SEND {hex(i)[2:]} 46'.encode()) t.recvuntil(b'> ') t.sendline(b'SEND d3 46') t.sendlineafter(b'> ', b'RECV 16') print(t.recvline()) t.interactive()s.py

af 02 df ed 8b c2 b8 58 2a e8 94 69 91 2e b9 6f was printed. I wrote yet another script to brute force the flag:

enc = b'\xaf\x02\xdf\xed\x8b\xc2\xb8\x58\x2a\xe8\x94\x69\x91\x2e\xb9\x6f' for i in range(65536): curr = i mask = 2**16 - 1 res = [] for i in range(16): curr = ((curr << 7) ^ curr) & mask curr = ((curr >> 9) ^ curr) & mask curr = ((curr << 8) ^ curr) & mask res.append(curr & 255) decoded = bytes([a ^ b for a, b in zip(res, enc)]) if decoded.startswith(b'TISC'): print(i) print(decoded)s.py

After running this script, the flag was printed!

TISC{hwfuninnit}

Closing thoughts

I think I got quite lucky in the course of solving this level, as many of my guesses proved to be correct.